Balancing Independence and Vulnerability of Older Adults | Part 1

“Balancing Independence and Vulnerability of Older Adults: What if Granny Wants to Gamble?” is a three-part special:

- Synopsis: An introduction and overview to lecture.

- Part 1 (this podcast): Discusses women’s differing longevity and the differences in how men and women manage finances later in life.

- Part 2: Will talk about elder financial abuse and the perpetrators.

- Part 3: The final part will recommend steps that lawyers can take to protect autonomy of older adults, especially women.

This is Susan Snyder, ACTEC Fellow from Chicago. Welcome to a special lecture series featuring Professor Mary Radford, ACTEC Fellow from Atlanta, Georgia.

Transcript/Show Notes

Thank you. I am going to start with a poem, or at least part of a poem. It’s called Warning by Jenny Joseph and it starts by saying:

When I am an old woman, I shall wear purple

with a red hat that doesn’t suit me and doesn’t go,

and I will spend my pension on brandy and on summer gloves and satin sandals

and say we have no money for butter.

Now, some of you might recognize this poem because in the 1990s, it spawned a whole society called the Red Hat Society. These are basically… let me show you a picture of these lovely ladies. These are women who have reached the age of 50 and are determined that they are going to enter the next phase of their lives with friendship, fulfilling their dreams, and a renewed outlook on life. They call themselves the Red Hat Society, obviously because they are modeling themselves after Jenny Joseph’s older woman. Now of course, we know that men would never join a society where they parade around in silly hats. How’d that get in there? Okay. Now to the serious part, thank you, Lee, for that contribution.

Our poet, Jenny Joseph, when she dresses her old woman in purple and red, she really foresees the conundrum that we are all facing now as we reach our older age and as we deal with older women in our society. So, she starts by dressing her woman in purple. In fact, the woman chooses to wear purple, and I am sure you know that the color purple historically has always been associated with power and with glory and with wealth — so much so that in Roman times only the highest level citizens were allowed to wear togas that even had purple borders. And Julius Caesar purportedly was the first emperor (though he would never call himself that) who was allowed to wear a toga that was completely purple.

But the color, the royal color purple, has not been completely relegated to men. In fact, there are lots of women, older women, who have worn that beautiful color and have had all of the power that goes with it. We have Queen Elizabeth I who, when she was crowned in 1558, wore a velvet mantle that was the color purple. And she actually followed the example of her father Henry the VIII by passing what were called Sumptuary Laws, and the Sumptuary Laws said that the only people who could wear any silk of the color purple were the king and the queen and the queen’s family.

And then, of course, Queen Victoria, queen of the United Kingdom of England and Ireland and empress of India; she reigned for 65 years and 216 days until she died at the age of 81. And she, like Elizabeth, gave her name to an era. And finally, we have Queen Elizabeth II. Doesn’t she look great in purple? She is now the longest reigning English monarch. She is in the 67th year of her reign and she is aged 92.

So, aging for women as well as for men has been a time, for some women at least, of power and wealth and glory. In fact, in our lifetimes, we have seen older women, at least figuratively, don this color of power. Golda Meir came out of retirement at the age of 71 to be elected the first woman Prime Minister of Israel. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf was 68 when she became the President of Liberia. She was the first woman head of state in Africa and also a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. Angela Merkel, who is now 64, was again the first female Chancellor of Germany and was Time magazine’s Person of the Year in 2015. And of course, four very strong and powerful women in the United States have donned the robe of power. Not exactly a purple one, but a black one. But these four women, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, all were at least age 50 at the time that they were appointed to the Supreme Court. And you probably know that Ruth Bader Ginsburg, just last week, celebrated her 86th birthday.

But there’s another side of aging and another side of aging for women. Unfortunately, for many older women in America today, it’s not a time of power. It’s not a time of glory and it’s not a time of wealth. So, Jenny Joseph also, you remember, has her older woman wear a red hat. Now red, on the other hand, is not associated with power. It’s often associated with passion and rage and even madness. So, when Jenny Joseph’s old woman thinks about what it’s going to be like, she’s thinking about being a little bit crazy or a little bit mad. Remember, she’s going to spend her pensions on brandy. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that!) And she’s going to wear pretty clothes instead of buying food. And she has additional plans. Here’s what Jenny Joseph tells us. Imagine how you would feel if you saw this woman.

I shall sit down on the pavement when I am tired

and gobble up samples in shops and press alarm bells

and run my stick along the public railings

and make up with the sobriety of my youth.

Now people worry when women act like this, particularly older women and rightfully they should, because sadly for many women in today’s world, they are suffering from the 20th century version of madness which is known as “neurocognitive disorder” or popularly, “dementia.” These older women are in fact increasing in our society on a day-to-day basis. So again, you might be wondering, why is she talking about this as a woman’s issue?

Statistics

You can wear terrible shirts and grow more fat

and eat three pounds of sausages at a go

or only bread and pickle for a week

and hoard pens and pencils and beer mats and things in boxes.

So, what happens today when an older woman decides that, for example that she wants to hoard pens and pencils and beer mats and things in boxes? Are we going to let her do that or are we going to call her “mad”?

Huguette Clark

So, like so many older women today, Huguette Clark was basically alone. She didn’t have a living spouse. She didn’t have any children. She had distant relatives, but she was reclusive, and she wouldn’t let those relatives come to see her. She expressed the fear, in fact, that everybody was after her money.

It is said that her dolls were her only companions. In fact, she hired an assistant to take care of the dolls and to bring, every once in a while, a few of the dolls for visits to the hospital. But despite being eccentric, as clearly, she was, Huguette Clark managed in the final years of her life to take care of all of her extensive property and assets with a great deal of meticulousness and with a very high level of financial capacity.

She was also a very generous woman. She gave many, many dollars to the hospitals that took care of her and to her caretakers. Now, Hadassah Peri was her favorite caretaker and, in fact, she did take care of Huguette Clark for those last 20 years of her life. So in return, Huguette gave her gifts of cash, like this check for 5 million dollars. And she gave her several residences and several cars, including a Bentley. So, when Huguette Clark died, she had about 300 million dollars left, and she left an additional 30 million to Hadassah Peri along with her doll collection. And she left the bulk of her estate to her arts foundation, of which her attorney and her accountant were going to be the trustees — for a sizable fee, as you might imagine. Ms. Clark’s distant relatives challenged the Will. Imagine that. They basically said that she was not of sound mind when she made that Will. And they said she was vulnerable and manipulated by her caretakers and by her accountant and by her attorney, and they cited her obsession with dolls as an example of the fact that she lacked capacity.

Well, the challenge to the Will was settled minutes before the jury was about to be chosen. So, we really don’t know. We don’t know for sure whether a jury would have found that Huguette Clark was of sound mind or instead that she lacked capacity and had been manipulated by all of these people around her; these people who, again, had been taking care of her. So, what happened? Well, in the settlement, Hadassah was allowed to keep the money that she’d already gotten, but she gave up the 30 million in the Will and the dolls. The distant relatives got 34.5 million dollars from her estate. And the rest went to her arts foundation, but her attorney and accountant did not serve as trustees.

So, this story is just an example of how older women sometimes might wish to indulge their eccentricities. But in doing so, they run the risk of having their freedom taken away from them. If it’s their physical freedom or their freedom to dispose of their property in any way that they want. And that happens because our society, and usually for all the right reasons, wants to protect these women from making bad decisions. Now, I don’t want to underestimate. I don’t want any of us to underestimate the severity of the problem of people being manipulated and people being abused.

Brooke Astor

Sara Cochran

So now I am going to tell you a story about a person you probably haven’t heard of. This is another wealthy woman. Her name is — lots of wealthy women — her name is Sara Cochran. She lived in Cobb County, Georgia, Marietta, Georgia and she was a grandmother who loved to gamble. And in fact, she won a lot, or at least she thought she did.

That’s the kind of scam that she was falling for over and over and over. And, an emergency conservator was appointed for her, and the emergency conservator said to the judge, “We have got to do something.” So, Ms. Cochran chose to take the stand at her own guardianship hearing, and she got on the stand and testified with acuity, with accuracy about her assets. She knew exactly what she was doing, but then she turned to the judge and said, “Your Honor, I need to leave because there’s a man from Jamaica and he’s waiting for me to call him because he’s got a check for me for 57 million dollars and two cars.” And so, the judge decided that she needed to have a conservator appointed for her.

Now the appointment of a conservator for somebody like Ms. Cochran has pretty draconian consequences. This means that she is no longer allowed to make her own decisions about how to spend her money. Now somebody else has been appointed to do it for her. So, Ms. Cochran appealed the court order that appointed the conservator for her, and the Court of Appeals of Georgia agreed with the probate court that, in fact, she did need a conservator. And they cited, again, various evidence, but then they said something that was really enlightened (and we don’t always use that term in the same sentence as Georgia courts.) But anyway, they said something that is really enlightening. They said that the mere fact that Ms. Cochran chose to play these fantasy games does not in and of itself mean that she needs a conservator. They said a person of perfectly sound mind, capable of understanding that the lotteries might be a fraud, nevertheless might choose to play the lotteries as escapist fantasy and fun. So, what the court is pointing out there is again the conundrum that we face. That conundrum is, how do we as a society protect the autonomy, the freedom of choice of women who do have sound minds and might just be eccentric or might just like to gamble? At the same time that we are protecting those other women who are vulnerable due to either dementia or outside forces, how do we balance these two things?

Warning

Well, we are finally paying attention, first of all, to elder abuse. And that is a good thing. Particularly, what I will be talking about today is elder financial abuse. But like — I don’t know if you remember the title of our poem — like our poet Jenny Joseph, I would like to issue a warning, and that warning is that we may be in the process of “overprotecting.” So, I am going to take a few moments today to reflect on the various aspects of elder financial abuse and I promise you that will be depressing. And, I am going to look at this in the context of three questions.

- First of all, what can the law do to protect the vulnerable at the same time that we are not unnecessarily jeopardizing the autonomy of people who don’t need to be protected?

- Second question, what can we as lawyers do to attain that balance?

- And the third question, what can everybody in this room do as individuals to help draw this appropriate balance between vulnerability and autonomy?

Gender Gap

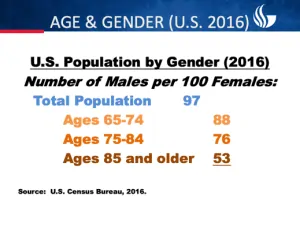

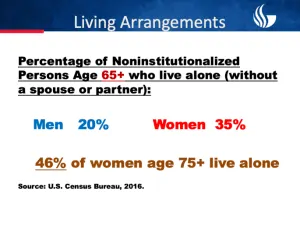

So, I am going to start by fleshing out one of the topics that I introduced a little bit earlier, and that’s this gender gap in the United States when it comes to aging. Now. there’s no secret that our population is graying. Let’s look around us. Okay? By the year 2030, 20 percent of our population will be aged 65 or older.

Americans who are aged 85 or older are the fastest growing demographic in the United States right now. So, in 1950 the average lifespan for an adult was 68.2 years. By 2018, the average lifespan for an adult was 10 years higher. That is 79.3 years. So, for men the average lifespan 77 years, for women the average lifespan is 81 years. Now, who am I talking about when I am talking about this group? Well, it’s actually a group that spans three generations. The GI Generation, and Tom Brokaw of course, immortalized them as the “Greatest Generation.” There are still many of them around, ages 95 and over. The Silent Generation, ages 74 to 94, and the Baby Boomers, about half of whom still do not believe that they are old, ages 55 to 73.

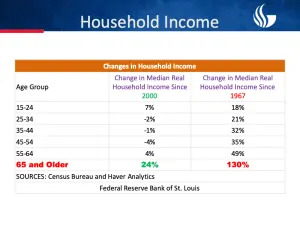

So right now, for the first time in American history, the highest median net worth is held by Americans who are aged 75 and older. Now, in addition to this being a wealthier group than the group that preceded it, this is a group of people who are actually going to be taking more responsibility for their finances and for their retirement. Some of you, I know, know that in prior generations, when an individual retired, usually thought of as a couple retiring, they were basically going to receive a pension from Social Security and probably from a defined benefit plan from their employer.

So in other words, the retiree and his spouse or her spouse knew that they had just a certain monthly budget. It was guaranteed, but that was what they had and they didn’t have to make any decisions about how to invest that money and they didn’t have to make any decisions about whether to withdraw or when to withdraw. It basically was all set out for them. But the retirees of today are facing a different kind of retirement. They are going to be dependent upon their own accumulations in things like profit sharing plans and 401K plans and individual retirement accounts. So, what does that mean? That means they are going to be the ones – not the government, not their employers – they are going to be the ones who have to make decisions about how to invest this money and when to withdraw it and how much to withdraw over time. Unfortunately, these nest eggs are viewed by the predators who are out there as a virtual pot of gold.

Financial Capacity

So, the financial security of individuals who are in this group that I am talking about is going to be linked very closely, much more closely than it has ever been, to their financial capacity. And by that, I mean basically, their “ability to manage their money to meet their needs in accordance with their values and then also in accordance with the amount of assets that they have.” And their financial stability is also going to be linked to their ability to protect themselves from the fraudulent activities of the scammers and fraudsters who are out there. So, basically only in the past six or seven years have researchers focused on this notion of financial capacity, and their findings are not optimistic.

One study shows us that basically financial capacity – again the ability to understand just the basics of what you need to know to invest and to project in terms of how much money you could take out – basic financial capacity on average declines at a rate of about 2 percent per year every year after age 60. Now, the other thing the study showed is that our confidence in our financial capacity does not decline. So, here’s a recipe for disaster. We have got the capacity declining, but we are perfectly confident that we know what we are doing. Okay, then add onto that the Wells Fargo study that talks about the naivete of Americans today. The study shows that basically one in five people aged 65 or over are going to be victims of fraud. One in 10 people are absolutely certain that that would never happen to them.

Now, in addition to all of that, there is a, I will call it a “personality trait” for lack of a better word, a personality trait that this generation or these generations are showing that doesn’t show so much in the younger generations. And that trait is basically being trusting of other people. In other words, on average, the older we get the more trusting we become of the people around us. So, this correlation between age and trust doesn’t seem to be tied to when we were raised or where we were raised. There’s a study that examined about 200,000 people in 83 different countries and saw this correlation. The older we get the more trusting we get. And there was even a study published in 2013 in Scientific American that found that actually there’s a physical reason. There’s a part of the brain that, when it ages ,becomes thinner, and that is the part of the brain that’s associated with assessment of risk and trust.

So basically, what are we seeing so far? What picture is shaping up? We have wealthy, older Americans living longer than ever before, handling their own retirement benefits, lessening financial capacity over time, sustained or increasing confidence in our financial capacity and we trust all the people around us. Okay. Need I say more? How do you spell VULNERABLE? And the worst part is that we have not even talked yet about the cognitive decline that comes with that madness I spoke about before, with dementia.

This concludes podcast Part 1 of 3 in our Special ACTEC Trust and Estate Talk. Please tune in for our next episode in the “Balancing Independence and Vulnerability of Older Adults: What if Granny Wants to Gamble?” series, which will discuss elder financial abuse and how the law can protect against abuses.

If you have ideas for a future ACTEC Trust & Estate Talk topics, please contact us at ACTECpodcast@ACTEC.org.

Latest ACTEC Trust and Estate Talk Podcasts

The Ethical Use of Artificial Intelligence in Trust & Estate Law

A law professor offers insights into the risks, rewards, duties and ethical considerations of lawyers using AI in their T&E practices.

What Is Artificial Intelligence and the Impact on T&E Law in 2024 and Beyond?

A primer on the types and uses of AI, then a deeper dive into the impact on trust and estate law from types to applications to ethical considerations.

The IRS Ruling on Modifying a Grantor Trust

Explore the gift tax implications for trust beneficiaries modifying grantor trusts in IRS CCA 202352018, with nuanced analysis and estate planning insights.